During the First World War, Patrick joined the London Irish Rifles (1/18th Battalion, The London Regiment), Soldier Number: A/1551, becoming a Sergeant. He was wounded at the Battle of Loos on 28 October 1915.

In the Preface to his book “The Amateur Army” (Herbert Jenkins, London, 1915) Patrick wrote:

“I am one of the million or more male residents of the United Kingdom, who a year ago had no special yearning towards military life, but who joined the army after war was declared. At Chelsea I found myself a unit of the 2nd London Irish Battalion, afterwards I was drilled into shape at the White City and training was concluded at St. Albans, where I was drafted into the 1st Battalion. In my spare time I wrote several articles dealing with the life of the soldier from the stage of raw "rooky" to that of finished fighter. These I now publish in book form, and trust that they may interest men who have joined the colours or who intend to take up the profession of arms and become members of the great brotherhood of fighters.

Patrick MacGill. "The London Irish," British Expeditionary Force, March 25th, 1915."

Patrick also wrote a novel based on his wartime experiences entitled “Children of the Dead End”.

After his recovery, Patrick was recruited into British military intelligence and wrote for MI 7b from 1916 until the Armistice in 1918.

In 1915, Patrick married Margaret C. Gibbons in London. They had three children, Christine, Patricia and Sheila MacGill. Patrick went to America on a lecture tour in 1930, remained in America in poor health and died in Florida, USA on 22nd November 1963. He was buried in Fall River, Massachusetts.

An annual literary event, the Patrick MacGill Festival, is held in his home town in his honour and a statue of him stands on the bridge where the main street crosses the river in Glenties.

Patrick MacGill’s WW1 poetry collection was published under the title “Soldier songs” (Jenkins, 1917) and he had poems published in ten WW1 anthologies. Here are some of his WW1 poems:

Death And Fairies

Before I joined the Army

I lived in Donegal,

Where every night the Fairies

Would hold their carnival.

But now I'm out in Flanders,

Where men like wheat-ears fall,

And it's Death and not the Fairies

Who is holding carnival.

A Lament From The Trenches

I wish the sea was not so wide that parts me from my love;

I wish the things men do below were known to God above!

I wish that I were back again in the glens of Donegal,

They’d call me a coward if I return but a hero if I fall!

Is it better to be a living coward, or thrice a hero dead?

It’s better to go to sleep, m’lad, the colour-sergeant said.

Before the Charge

The night is still and the air is keen,

Tense with menace the time crawls by,

In front is the town and its homes are seen,

Blurred in outline against the sky.

The dead leaves float in the sighing air,

The darkness moves like a curtain drawn,

A veil which the morning sun will tear

From the face of death. – We charge at dawn.

Back At Loos

The dead men lay on the shell-scarred plain,

Where death and the autumn held their reign

Like banded ghosts in the heavens grey

The smoke of the conflict died away.

The boys whom I knew and loved were dead,

Where war's grim annals were writ in red,

In the town of Loos in the morning.

Sources: Find my Past

Catherine W. Reilly “English Poetry of the First World War: A Bibliograph” (St. Martin’s Press, New York, 1978) p. 211.

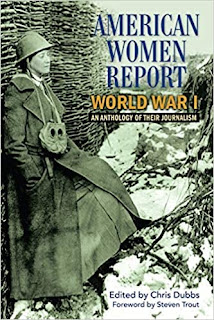

Photo of Patrick in WW1 from his book “The Amateur Army” (Herbert Jenkins, London, 1915)

https://www.gutenberg.org/files/16078/16078-h/16078-h.htm

http://www.ricorso.net/rx/az-data/authors/Mac/M-Gill_P/life.htm